What is that, Truth? The Truth of all three is only one. It is expressed at various locations in the Upaniṣads.

ईशा वास्यं इदं सर्वं, īśā vāsyaṃ idaṃ sarvaṃ, all this is pervaded by the supreme imperishable Reality. (ईश उपनिषद्, Īśa Upaniṣad 1).

One Truth is perceived in infinite forms. That is, one Truth manifests in unlimited forms.

सर्वं खल्विदं ब्रह्म्, sarvaṃ khalvidaṃ brahm, all this, no doubt, is Brahman. (छांदोग्य उपनिषद्, Chāndogya Upaniṣad 3.14.1)

The one that provides the vision of that Truth is the Sanātana Dharma, the Sanātana Vaidika Dharma, or the Hindū Dharma. Whatever is there, whatever exists, whether perceptible or imperceptible, is only the abhivyakti (अभिव्यक्ति, expression) – the manifestation of the supreme imperishable Reality. To provide the vision of that Truth, Veda–Śāstra has provided a vision of life and a way of life. In that vision of life, the fourfold Puruṣārtha (पुरुषार्थ, object of human pursuit): Dharma (धर्म), Artha (अर्थ), Kāma (काम), and Mokṣa (मोक्ष) are provided. In the way of life, the Varṇāśrama (वर्णाश्रम) System is provided, consisting of the fourfold functional classes: Brāhmaṇa (ब्राह्मण, knowers of the Brahman who impart knowledge), Kṣatriya (क्षत्रिय, providers of security), Vaiśya (वैश्य, engagers in commerce), and Śūdra (शूद्र, providers of labor) and the four stages of life: Brahmacarya-āśrama (ब्रह्मचर्य-आश्रम, bachelor student stage), Gṛhastha-āśrama (गृहस्थ-आश्रम, householder stage), Vānaprastha-āśrama (वानप्रस्थ-आश्रम, retired stage), and Saṃnyāsa-āśrama (संन्यास-आश्रम, renunciation stage). Bhagavāna Śrī Kṛṣṇa (भगवान श्री कृष्ण) in Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā (श्रीमद् भगवद् गीता) 4.13 has said -चातुर्वर्ण्यं मया सृष्टं गुणकर्मविभागशः, cāturvarṇyaṃ mayā sṛṣṭaṃ guṇakarmavibhāgaśaḥ, the fourfold functional class system (Catura–Varṇa) was created by Me according to the distinctions of the constituents (गुण, guṇa) and actions (कर्म, karma) of Prakṛti.

In the fourfold Puruṣārtha, Dharma is the means (साधन, sādhana). Mokṣa is the ultimate objective. Mahākavi Kālidāsa (महाकवि कालिदास) in his great poem “Kumārasambhava (कुमारसम्भव),” 5.33, has said that शरीरमाद्यं खलु धर्मसाधनम्, śarīramādyaṃ khalu dharmasādhanam, the body is the means for Dharma. Therefore, every act done through the body, senses, mind, and intellect ought to be done by Dharma. They should be done as Śāstra enjoined moral duty (कर्तव्य, kartavya). Pursuing Artha (wealth) and Kama (desire) only gives transient happiness, though, in the end, the result is only unhappiness. That is why they are not beneficial (श्रेय, śreya) but are just dear (प्रेय, preya). Therefore, both acquisition of wealth (Artha) and fulfillment of desires (Kama) ought to be done righteously (धर्ममय, dharmamaya) by Śāstra enjoined principles.

The system of Varṇāśrama naturally evolved to maintain the sustainability of society. It is not an artificial system but refers to natural classifications that appear to various degrees in all humanities. From the Vedantic perspective personality or nature of individuals are varied based on the extent of goodness, purity, virtuosity (सात्विक, sātvika), passion (राजसिक, rājasika), and sixfold mutations viz. lust, anger, greed, delusion, excessive pride, and envy (तामसिक, tāmasika) constituents present in their personality, and thus their suitability for distinct professional duties and activities. Individuals have different innate tendencies for work and exhibit a variety of personal attributes. There are also natural phases in life when performing certain activities is easier and more rewarding. Individuals best realize their potential by considering such natural arrangements and that society should be structured and organized accordingly.

It should be remembered that the functional classifications were not intended to represent the superiority of one over the other. The distribution of activities was based on one’s nature, on one’s intrinsic attributes rather than birth in those functional classifications. The classes were not considered higher or lower among themselves. Each Varṇa and Āśrama had its own specified function. What may be desirable for one section of society may be degrading for another. For example, absolute non-violence, which includes refraining from animal sacrifice, is essential for the priestly class but considered wholly unworthy of a Kṣatriya. Generating wealth and producing children are necessary for householders, but intimate contact with money and women is spiritually suicidal for the renouncer. Underlying all these apparent differences was the common goal of advancing in spiritual life based on Sanātana–Dharma. Since the center of society was the supreme imperishable Reality, everyone worked according to their intrinsic attributes to sustain themselves and the community; and make their life a success by progressing towards realizing the supreme imperishable Reality. Thus, in the system, there was unity in diversity. Diversity is inherent in nature and can never be removed. We have various limbs, and they all perform different functions. Expecting all limbs to perform the same functions is futile. Seeing them all as different is not a sign of ignorance but factual knowledge of their utilities.

Similarly, the variety among human beings cannot be ignored. Party leaders formulate ideologies even in communist countries where equality is the foremost principle. The military wields guns and protects the nation; farmers cultivate the land, and industrial workers do mechanical jobs. The four classes of occupations exist there, despite all attempts to equalize. The Varṇāśrama system recognized the diversity in human nature and scientifically prescribed duties and occupations matching people’s nature. Unfortunately, the Varṇāśrama system is maligned today and has lost its original intent. It is viewed as a social class or a caste system, anglicized from Portuguese “casta,” who came to India in the late fifteenth century and propagated an erroneous view of the Varṇāśrama system to convert Indians to Christianity. Today, people continue to wrongly assign functional class as caste based on birth when in reality, the original intent was the assignment by Karma Saṃskāra (कर्म संस्कार).

Earlier, the ultimate Puruṣārtha, the supreme goal described, was Mokṣa. So, what is Mokṣa? Mokṣa means liberation. But liberation from what? In simple terms, liberation means freedom from Bandhana (बन्धन, bondage). Bondage of what? That bondage is not physical. It is only this – human beings perceive themselves to be extremely unhappy (दुःखी, duḥkhī). Liberation is to be free from unhappiness (दुःख, duḥkha). One inflicted with pain and suffering desires freedom (निव्रुत्ति, nivrutti) from that duḥkha, that is, the complete (अत्यन्त, atyanta) freedom from pain and suffering and the attainment (प्राप्ति, prāpti) of eternal (नित्य, nitya) and immovable (अचल, acala) happiness (सुख, sukha). Individuals have a sense of incompleteness, physical incompleteness, and undoubtedly emotional incompleteness. There is an ongoing sense of inadequacy centered on “I,” the self. The vision that removes the incompleteness and inadequacy in humans is the Sanātana Vaidika Dharma. That vision is provided in the Vedas and Upaniṣads and synthesized in the Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā. In the fourth verse of the Gītā Dhyāna (गीता ध्यान,) it is said –

सर्वोपनिषदो गावो दोग्धा गोपाल नन्दनः, पार्थो वत्सः सुधीर्भोक्ता दुग्धं गीतामृतं महत्, sarvopaniṣado gāvo dogdhā gopāla nandanaḥ, pārtho vatsaḥ sudhīrbhoktā dugdhaṃ gītāmṛtaṃ mahat, all the Upaniṣads are cows. Śrī Kṛṣṇa is a milker. Arjuna is a calf. Wise and pure men drink the milk, the supreme immortal ambrosia of the Bhagavad Gītā.

Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā provides the means to attain eternal and immovable happiness and the complete removal of pain and suffering (दु:ख, duḥkha). The quest for perfection and completeness is not something one must go somewhere to get it. Wherever one is, however one is, one is indeed complete. Eternal and immovable happiness is one’s true nature (स्वरूप, svarūpa). It is a definite tenet of Vedānta (वेदान्त)that, though the true nature of a Jīva (जीव),is Asti-Bhāti-Priya (अस्ति-भाति-प्रिय),and it is always attained (नित्य प्राप्त, nitya prāpta) yet due to impurity (मल, Mala), vacillations (विक्षेप, Vikṣepa)and shrouding (आवरण, Āvaraṇa)– the three faults (दोष, Doṣa) residing in the conscience, Jīva has a perception of non-attainment and separateness. The issue is only ignorance. Ignorance of not knowing one’s true nature, Ātma ajñāna (आत्म अज्ञान). The Mahāvākya (महावाक्य) of Chāndogya Upaniṣad 6.8.7, तत् त्वम् असि, tat tvam asi, that thou art, enlightens one that “what you are looking for is in yourself.” The cause of the perception of non-attainment and separateness is the ignorance of not knowing one’s true nature, the nature of one’s Ātmā. When knowledge is acquired, ignorance naturally vanishes. So, what is the nature of knowledge? The nature of knowledge is twofold. First, knowledge is objective. That is, it is based on the object (वस्तुतन्त्र, vastutantra). One gets knowledge of just how the thing is. If an object is black, one will only know it in black form. Second, knowledge will happen only when there is an activity of doubtless irrefutable knowledge (प्रमाण व्यापार, pramāṇa vyāpāra).

Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā, as the Brahma Vidyā (ब्रह्म विद्या), provides Upadeśa (उपदेश, spiritual guidance), knowledge (ज्ञान, jñāna) of the true nature of the Ātmā (आत्मा). It provides the knowledge that the true nature of the Ātmā is Asti-Bhāti-Priya. It is the Jagat Kāraṇa (जगत् कारण, cause of the universe). It is abhinna (अभिन्न, non-distinct) from Īśvara, the supreme imperishable Reality, the Brahman (ब्रह्मन्). As stated in Ṛgveda 4.26.1, अहम मनुः अभवम्, ahama manuḥ abhavam, I have been Manu. I am everything. I am beyond time and space. I am beyond the reach of words and the mind (अवाङ्मनसगोचर, Avāṅmanasagocara). No one is capable of describing it through words and speech.

When Upadeśa is heard from a realized preceptor (योग्य आचार्य, yogya ācārya), knowledge is acquired right at the time it is heard. That is why in Gītā 18.73, Arjun says, नष्टो मोह: स्मृतिर्लब्धा त्वत्प्रसादान्मयाच्युत, naṣṭo mohaḥ smṛtirlabdhā tvatprasādānmayācyuta, Hey Śrī Kṛṣṇa, the infallible one! With Your grace, my confusion is dispelled, and I have regained memory. The issue was only of confusion (मोह, moha). Earlier in Gītā 2.7, Arjuna expressing his confusion, had asked Śrī Kṛṣṇa, पृच्छामि त्वां धर्मसम्मूढचेताः, pṛcchāmi tvāṃ dharmasammūḍhacetāḥ, I am asking You, (because) my mind is confused about duty. It is reasonable to question why knowledge does not happen. The root obstacle is Avidyā (अविद्या, ignorance). However, secondary barriers must be addressed before the root obstacle is addressed. For instance, when a diabetic patient has to undergo hernia surgery, it is necessary that a regular hernia operation cannot be started until his blood sugar and pressure are met. Likewise, knowledge is not acquired until there is the purity of the conscience and there is ekāgratā (एकाग्रता, concentration) of the mind in the self. Gītā, as the Yoga Śāstra (योग शास्त्र), provides means to acquire purity of the conscience and concentration of the mind. It provides means for individuals to remove the faults resident in the conscience and make one Adhikārī (अधिकारी, fit) for knowledge. Acquisition of the purity of the conscience, attaining perfection, enables one to realize the true nature of the self. Upon Self-Realization, eternal and immovable happiness and complete removal of pain and suffering are gained while alive. At that time, as said in Gītā 2.70, आपूर्यमाणमचलप्रतिष्ठं समुद्रमाप: प्रविशन्ति यद्वत्, तद्वत्कामायं प्रविशन्ति सर्वे स शान्तिमाप्नोति न कामकामी, āpūryamāṇamacalapratiṣṭhaṃ samudramāpa: praviśanti yadvat, tadvatkāmāyaṃ praviśanti sarve sa śāntimāpnoti na kāmakāmī, just as water enters an immovable ocean filled from all sides, in the same way in whom all desires enter, he attains peace and not the one who desires sense objects. For such an individual as said in Gītā 3.17, यस्त्वात्मरतिरेव स्यादात्मतृप्तश्च मानव:, आत्मन्येव च सन्तुष्टस्तस्य कार्यं न विद्यते, yastvātmaratireva syādātmatṛptaśca mānava:, ātmanyeva ca santuṣṭastasya kāryaṃ na vidyate, however, that person who solely rejoices in the Self, who is content in the Self, and who is satisfied solely in the Self, for him, there is no duty. Upon reaching such state, as said in Gītā 2.72, एषा ब्राह्मी स्थिति: पार्थ नैनां प्राप्य विमुह्यति. स्थित्वास्यामन्तकालेऽपि ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृच्छति, eṣā brāhmī sthiti: pārtha naināṃ prāpya vimuhyati. sthitvāsyāmantakāle’pi brahmanirvāṇamṛcchati, Hey Arjuna! This is the state of Brahman. By attaining it, one does not get deluded. Even if one is in this state at the time of death, one attains Nirvāṇa-Brahma.

- Artha (अर्थ) means the instruments for the sustenance of life and incorporates wealth, career, activity to make a living, financial security, and economic prosperity. Its typical use is regarding wealth, material, or worldly possessions. It is also used to express purpose or aim.

- Kāma (काम) signifies lust, desire, passion, or pleasure of the senses. It is an internal force that produces an intense desire for something or circumstance while already having a significant amount of the desired object. It can take any form, such as the lust for sexuality, money, or power. It can take such mundane forms as the desire for food as distinct from the need for food or the passion for redolence when one lust for a particular smell that brings back memories.

- Mokṣa (मोक्ष) means liberation, the attainment of eternal (नित्य, Nitya) and immovable (अचल, Acala) happiness (सुख, Sukha) and complete (अत्यन्त, Atyanta) removal (निव्रुत्ति, Nivrutti) of pain and suffering (दु:ख, Duḥkha) is Mokṣa. Alternatively, attainment of the Brahman and freedom from the bondage of the Saṃsāra (संसार, world) is Mokṣa, meaning liberation from the world of transmigrating lives and attainment of the supreme-bliss (परमानन्द, Paramānanda).

- The qualities of a Brāhmaṇa, as provided in BG 18.42 Brahma-Prakṛti (ब्रह्म-प्रकृति), are: control of the mind, restraint of the senses, austerity, purity, forgiveness, simplicity, faith in preceptors and scriptures, knowledge of the scriptures, and realized knowledge.

- The qualities of a Kṣatriya, as provided in BG 18.43 Kṣātra-Prakṛti (क्षात्र-प्रकृति), are valor, splendor, fortitude, skill, charity, leadership attribute, and not fleeing in war.

- The qualities of a Vaiśya, as provided in BG 18.44 Vaiśya-Prakṛti (वैश्य-प्रकृति), are agriculture, protection of cows, and commerce.

- The qualities of a Śūdra, as provided in BG 18.44 Śūdra-Prakṛti (शूद्र-प्रकृति) is serving through labor.

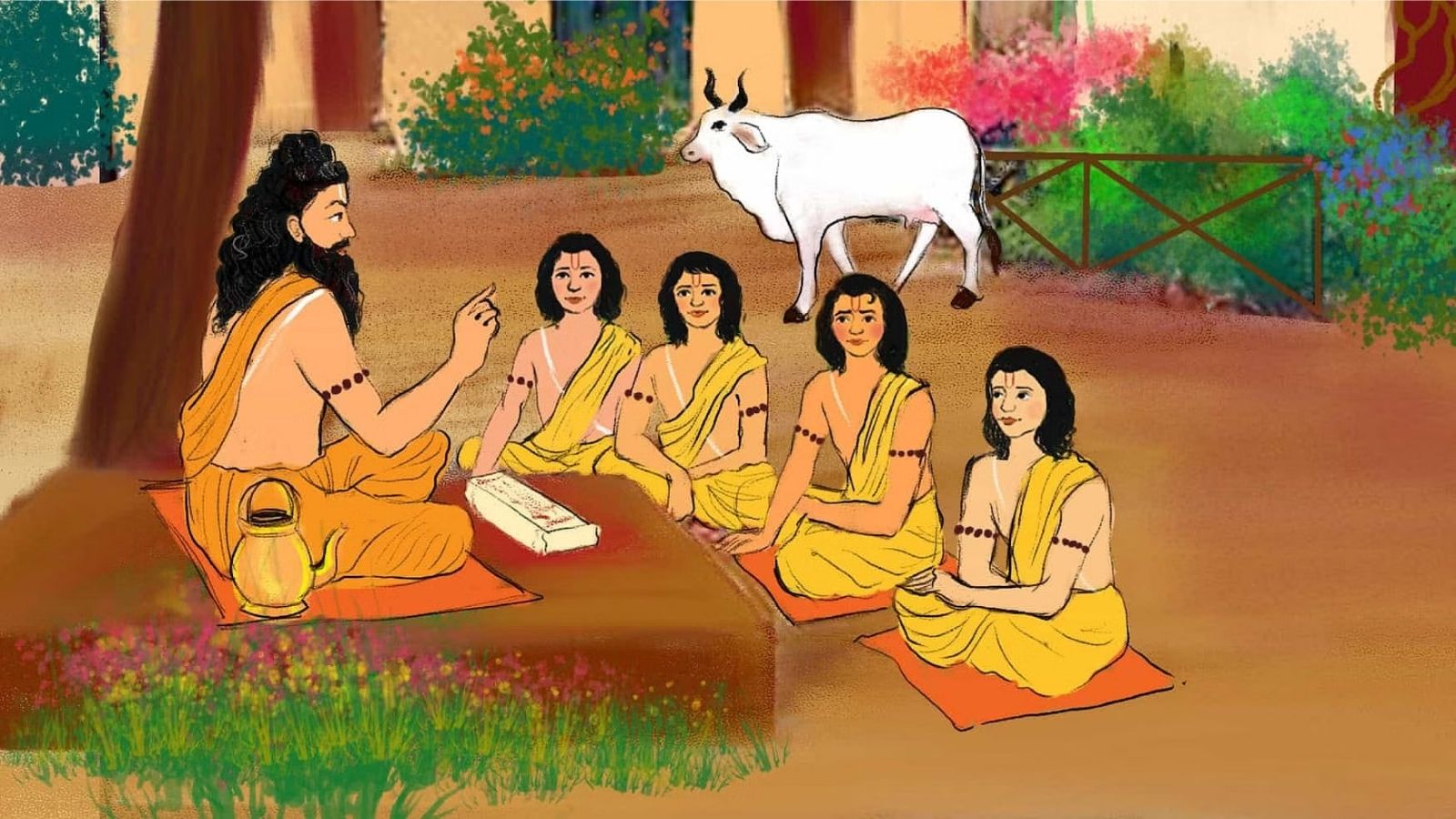

- Brahmacarya-āśrama means the first bachelor student stage of life from childhood to around 25. This stage focuses on education and includes the practice of celibacy. In Vaidika times, students went and lived in a Gurukula (गुरुकुल, house of a preceptor), acquiring knowledge of science, philosophy, scriptures, and logic, practicing self-discipline, working to earn remuneration (दक्षिणा, dakṣiṇā) to be paid to the preceptor, and learning to live a life of Dharma (righteousness, morals, duties).

- Gṛhastha-āśrama means the second stage of an individual’s married life, from the age of 25 to the age of 50, with the duties of maintaining a household, raising a family, educating own children, and leading a family-centered and virtuous social life. The householder stage is considered the most important of all stages in a sociological context. Human beings in this stage not only pursue a moral life, but they also produce food and wealth that sustain people in other stages of life and the continuation of progeny. The stage also represents where the most intense physical, sexual, emotional, occupational, social, and material attachments exist in a human being’s life.

- Vānaprastha-āśrama means one who gives up worldly life or literally retires to the forest. In this third stage of life, from the age of 50 to 75, a person hands over household responsibilities to the next generation, takes an advisory role, and gradually withdraws from the world. It is a transition phase from a householder’s life with a greater emphasis on wealth, pleasure, and desires to one with a greater focus on spiritual liberation.

- Saṃnyāsa-āśrama means the last stage of life marked by the renunciation of material desires and prejudices, represented by a state of disinterest and detachment from material life, generally without any meaningful property or home, and focused on liberation, peace, and simple spiritual life. Anyone could enter this stage after completing the Brahmacarya stage of life.

- Vedānta means “the end of the Vedas,” and reflects ideas espoused in the Upaniṣads (उपनिषद्), specifically, knowledge and liberation.

- Jīva means the conscious element in the body who is the doer-enjoyer. It is the embodied Ātmā (आत्मा), i.e., the delimited Ātmā. It is the pure Ātmā on whom I-ness sense of the body, senses, mind, and intellect are superimposed due to nescience. It has also been referred to as Jīvātmā (जीवात्मा), Dehī (देही), Śarīrī (शरीरी), Jīva-Sākṣī (जीव-साक्षी), Soul, or Spirit. Just as there is no distinction between the space enclosed in a pot and the pervasive space, and upon the destruction of the pot is only the pervasive space. Likewise, there is no distinction between a pure Jīva and the Paramātmā (परमात्मा, the supreme imperishable Reality).

- Asti-Bhāti-Priya means the Existent-Conscious-Bliss. Asti means the sense of perpetual existence, the sense of Astitva (अस्तित्व, existence, of being), the sense of Sat (सत्, real). Bhāti means the sense of knowledge, illumination, wisdom, the sense of consciousness (भातित्व, Bhātitva). Priya means the sense of happiness or Ānanda (आनन्द, bliss). Asti-Bhāti-Priya is synonymous with Saccidānanda (सच्चिदानन्द, Real Conscious Bliss), a compound word from Sat (सत्), meaning that which is the real, existent, or true essence, Cit (चित्), meaning the conscious element, and Ānanda meaning bliss. All three are considered inseparable from the nature of the supreme imperishable Reality or the Brahman.

- Mala (मल) means impurity, dirt.

- Vikṣepa (विक्षेप) means vacillations, the tossing of the mind which obstructs concentration of the mind.

- Āvaraṇa (आवरण) means the veil of ignorance.

Editor’s note: This is the concluding part of the two-part article.

![[New India Abroad] Shri Ram Janma Bhumi Murti Pran Pratishtha](https://hinduvishwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/shree-ram-murti-pranapratistha-75x75.jpeg)

![[ India Today ] Ohio senator JD Vance thanks wife, a Hindu, for helping him find Christian faith](https://hinduvishwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/us-senator-jd-vance-reveals-how-his-hindu-wife-usha-helped-him-find-his-christian-faith-image-re-272530504-16x9_0-120x86.webp)