Introduction

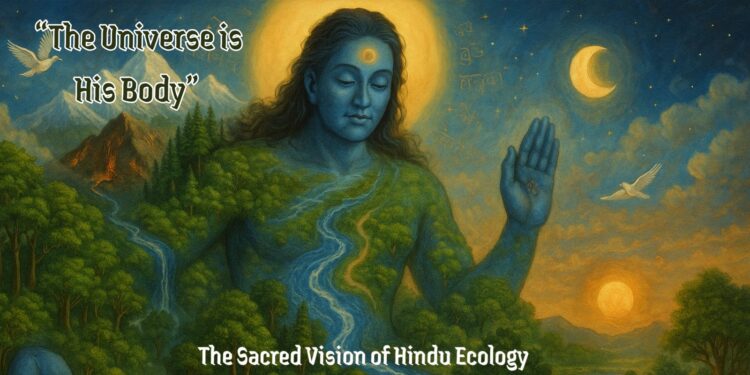

“The air is his breath, the trees are the hairs of his body, the oceans his waist, the hills and mountains are his bones, the rivers are the veins of the Cosmic Person.” This profound anthropocosmic imagery from the Atharva Veda [1] reveals the foundational principle of Hindu ecology: that the natural world is not an inert resource but a sentient, sacred entity, the living embodiment of the divine. Within this ancient darśana, or worldview, an intrinsic environmental sensitivity is not an ancillary feature but constitutes its very core.

This ecological ethos is no modern reinterpretation but is woven into the tradition’s metaphysical fabric, articulated through scripture, philosophy, and ritual. The Pañcamahābhūta, the five great elements – earth (Pṛthvī), air (Vāyu), water (Jala), fire (Agni), and space (Ākāśa) – are understood as the consecrated building blocks of the cosmos, central to both grand cosmology and daily rites [2]. This worldview transforms the physical landscape into a sacred cartography, where rivers like the Gaṅgā, trees like the Peepal, and mountains like Kailash are revered as living manifestations of divinity, fostering a deep-seated ethic of protection. Yet, a profound dissonance exists between this sacred ideal and contemporary reality. Certain modern practices, such as the immersion of idols laden with toxins and the use of chemical colors in festivals, have created ecological catastrophes. This adharmic behavior, born of commercialism and a decay in civic responsibility, attracts condemnation that mistakenly targets the religion itself, when the actual cause is a perversion of its traditions.

As the global community grapples with unprecedented environmental collapse, this ancient yet living worldview offers a potent spiritual and ethical framework for re-evaluating humanity’s relationship with the planet. This article examines how Hindu philosophy, sacred literature, and ritual practices cultivate a deep-rooted environmental ethic by portraying nature as divine and interconnected with human life; it also explores how contemporary eco-conscious efforts are working to reform environmentally harmful traditions by realigning them with the original principles of Hindu dharma – principles that emphasize sustainability, reverence for the natural world, and a collective responsibility to preserve it.

Hindu Dharma’s Reverence for Nature

Deities and Natural Elements

Hindu Dharma’s spiritual worldview finds profound expression in its personification of nature’s forces as divine entities. Far from being mere abstract symbols, these deities are the sacred embodiments of elemental phenomena, each signifying a critical dimension of both ecological equilibrium and cosmic order. Varuna, the sovereign of the celestial waters, governs not only oceans, rivers, and rainfall but also upholds Rta. This universal law inextricably links the hydrological cycles to the ethical and spiritual integrity of the cosmos. His dominion thus sanctifies the element of water itself, mandating a reverential and restrained approach to its use. In a similar vein, Agni, the god of fire, serves as the alchemical agent of transformation and purification; as the consecrated medium for transmitting offerings to the celestial realm, he is central to Hindu ritual. Agni’s dual presence in domestic hearths and sacred altars underscores the purifying power of flame and the symbiotic necessity of maintaining both spiritual and environmental purity. As the god of air, Vayu manifests as the universal life force, the very prana or cosmic breath that animates and connects all beings, a conception that asserts a theological basis for preserving atmospheric balance. The Earth is venerated as the goddess Prithvi, a nurturing matriarch who sustains all life and is perceived not as inert ground, but as a living, sentient being that demands worship. This maternal framing of the Earth cultivates a profound ethic of stewardship, grounded in principles of filial care and ecological restraint.

Collectively, these elemental deities reveal a sophisticated theology that intrinsically weaves the natural world into its spiritual fabric. Reverence for air, water, fire, and earth is therefore not an optional virtue but an ontological imperative, mandated by dharma and enacted in the rhythms of daily devotional life.

Sacred Natural Sites

Beyond the personification of the elements, Hindu cosmology transfigures the physical landscape itself, revering specific natural features as direct manifestations of divine presence and thereby elevating geography into sacred space. Rivers such as the Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati are not merely watercourses but are venerated as living goddesses [3]. The Ganga, for instance, functions as both a soteriological and ecological lifeline, a divine matriarch whose waters are believed to purify sin and liberate the soul, thereby absolving the karmic burdens of those who perform ritual bathing. This symbolic gravitas, rooted in Vedic and Puranic traditions, extends to other sacred rivers as well. Similarly, mountains, particularly the Himalayas, are consecrated as the terrestrial abodes of gods and sages. Mount Kailash, famously associated with Lord Shiva, is conceived as the axis mundi, the spiritual pivot of the entire universe, transforming these mountains from geological features to sacred abodes, reinforcing their spiritual importance in Hindu cosmology [4]. This sacred geography also extends to the botanical realm, where trees such as the Peepal, Banyan, and Tulsi are revered as divine presences. The Peepal tree is considered a dwelling place of Lord Vishnu, the Banyan symbolizes eternal life with its expansive, temple-like form, and the Tulsi plant is a fixture of daily household devotion to Goddess Lakshmi. Rituals such as Vriksha Bandhan, where devotees tie protective threads around trees, formalize a covenant of respect, affirming the belief in flora as sentient entities deserving protection [5].

These natural features – rivers, mountains, and trees – thus function as living conduits, portals between the human and divine realms. Their consecrated status fosters a deep-seated environmental ethic that reframes the human relationship with nature. Within this sacred cartography, polluting a river or exploiting a forest is not merely an ecological misdeed; it is a spiritual transgression, an act of sacrilege against the divine itself.

Scriptural Evidence

Hindu Dharma’s sacred literature articulates a sophisticated ecological theology, one in which the natural world is conceived not as an inert backdrop for human drama but as a vibrant, holy sphere imbued with divine significance. Across the Vedic hymns, the metaphysical discourses of the Upanishads, and the ethical teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, the scriptures forge an unassailable link between the divine, nature, and humanity, framing environmental stewardship as a sacred obligation. This worldview finds one of its earliest and most poignant expressions in the Atharva Veda [6]. The evocative Bhumi Sukta addresses the Earth not as an object of dominion but as a mother, establishing a principle of ecological reciprocity: “Mother Earth, may whatever I dig from you grow back again quickly, and may we not injure you by our labour” (Atharva Veda 12.1.35) [7]. This plea for reverent, regenerative use presents an ancient conception of sustainability. This vision is expanded in the Purusa Sukta, which posits the entire universe as the physical body of the cosmic being, the Virat Purusa, where mountains are his bones, rivers his veins, and trees the hairs on his body [8]. This profound anthropocosmic metaphor dissolves any perceived separation between humanity and the environment, reconceiving ecological destruction as a direct violation of the divine anatomy: an act of adharma against the cosmic order, or rta.

This principle of sacred interconnectedness achieves even greater metaphysical depth in the Upanishads, where the ontological unity of all existence becomes the central theme. The declaration Sarvam khalvidam brahma (“All this is Brahman”) from the Chandogya Upanishad [9] provides the ultimate foundation for an environmental ethic, for if the Supreme Reality pervades every particle of the universe, then to pollute or exploit nature is to defile Brahman itself [10]. The Isa Upanishad builds upon this by mandating a specific code of conduct, stating that the world is “pervaded by the Lord” (Isavasyam idam sarvam) [11]. This notion leads directly to an ethic of tyaga, or renunciation, exhorting individuals to enjoy the Earth’s riches not with greed, but with reverent restraint, taking only what is necessary. This frames ecological consciousness as a direct extension of religious piety.

The Bhagavad Gita further reinforces these themes, weaving them into a comprehensive framework of duty (dharma). Lord Krishna explains that creation is sustained through yajña, a covenant of sacrificial reciprocity binding humanity and the natural world (prakruti) in a cycle of mutual care [12]. Here, yajña symbolizes a cosmic economy of give-and-take, a foundational principle of ecological balance that must be honored through offerings and restrained use. Later, Krishna’s declaration that “Vasudeva is all” (Vasudevah sarvam iti) [13] powerfully echoes the Upanishadic theme of unity, asserting the immanence of the divine in all creation. This perspective transforms environmental degradation from a mere sociopolitical problem into a profound spiritual crisis, for when the environment is harmed, it is the divine body itself that suffers. Fulfilling one’s personal duty (svadharma) thus becomes inseparable from the ecological responsibility to uphold the health of prakruti.

Together, these scriptural teachings constitute a formidable and cohesive theological framework for environmental stewardship. From the Vedic reverence for a maternal Earth to the Upanishadic realization of cosmic unity and the Gita’s call for dharmic action, this tradition does not merely encourage environmental protection: it sanctifies it as an inviolable spiritual duty.

Philosophical Concepts

Beyond scriptural injunctions, the Hindu ecological ethos is profoundly shaped by a sophisticated ethical architecture that governs moral conduct and metaphysical worldview. Core tenets such as ahiṃsā (non-violence), dharma (righteous duty), and ṛta (cosmic order) converge to form an integrated system of spiritual ecology, one that posits a sacred responsibility toward all of existence. This framework is not merely prescriptive but is rooted in the soteriological goal of mokṣa (liberation), rendering ecological harmony essential for spiritual progress.

Foremost among these tenets is ahiṃsā, the paramount dharma of non-violence, which extends its compassionate embrace beyond humanity to encompass every form of life (jīva). This principle is anchored in the metaphysical realization that the singular, eternal Self (Ātman) is immanent in all beings, from the smallest insect to the largest mammal. From this radically non-dual (Advaitic) perspective, harming any creature or element of the natural world (Prakṛti) is an act of spiritual ignorance (avidyā), a self-inflicted wound born from the delusion (moha) of separateness [14].

Ahiṃsā is thus transformed from a mere moral commandment into an ontological imperative, promoting a profound harmony with the biosphere and demanding opposition to any exploitative practice that inflicts violence upon the manifest body of the divine [15].

This principle is inextricably linked to dharma, derived from the Sanskrit root dhṛ, meaning “to sustain.”

Dharma is the universal principle that upholds and maintains cosmic stability; it is not simply a personal virtue but the duty to act in alignment with the broader cosmic order (ṛta).

Ṛta is the intricate, rhythmic, and moral law governing the universe, and to live a dharmic life is to attune oneself to its sacred patterns, from agricultural cycles to seasonal festivals. Consequently, actions driven by greed (lobha) and overconsumption constitute acts of adharma. Such ecological negligence actively disrupts ṛta, introducing a state of imbalance and decay (vikṛti) that generates negative karma and causes suffering across all realms.

These philosophical tenets are not meant to exist in abstraction but are to be actualized through a dedicated praxis (sādhana). The metaphysical emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life is enacted through virtues that function as spiritual disciplines.

Aparigraha (non-possessiveness) offers a practical antidote to the consumerist mindset, while satya (truthfulness) prompts one to perceive the ultimate reality of divine unity in nature. Most importantly, sevā (selfless service) rendered to the environment, through conservation and restoration, becomes a form of karma yoga. This offering purifies the individual while helping to restore cosmic balance. These virtues guide adherents toward a modest and respectful existence, reinforcing the view that the Earth is not a resource to be plundered but a divine partner in the sacred cycle of life.

Rituals and Practices

The ecological consciousness of Hindu Dharma is not confined to scripture or abstract philosophy; it finds its most vibrant and kinetic expression in the everyday rituals (pūjā) and festival practices that celebrate and honor the natural world. These rituals function as a form of performative theology and ecological enactment, reinforcing the sanctity of Prakṛti through both symbolic and practical means. Through these consecrated acts, or samskāras, the philosophical principle of divine immanence becomes a lived reality. For instance, the practice of Vriksha Bandhan involves tying sacred threads around trees, symbolizing a covenant of protection and reverence between humans and the botanical world. This ethos is institutionalized in the tradition of devara kadu, or sacred groves, which function as biodiversity hotspots protected not by secular law but by a religious mandate that views the forest itself as a temple [16].

This ritual alignment extends to the grand cycles of time (kāla) and seasons (ṛtu), with major festivals designed to synchronize human life with cosmic rhythms. Harvest festivals like Pongal in the south and Baisakhi in the north are elaborate ceremonies of gratitude, honoring the Sun God (Sūrya), the Earth (Bhūmi), and the farm animals whose combined energies sustain human life. Among indigenous communities, festivals like Sarhul explicitly worship the divine essence within specific flora, highlighting the deep animistic and nature-centric roots of broader Hindu ritual life. Initially, these festivals exemplified sustainable living, promoting the use of local, biodegradable materials and foods in a manner that generated minimal waste, embodying a truly sāttvic (pure and harmonious) mode of celebration.

Through these consecrated acts, the abstract principles of dharma and ecological reciprocity become tangible, lived realities, cyclically reaffirming the sacred bond between humanity and Prakrti.

Addressing the Counterargument

Despite the profound ecological ethos embedded in Hindu scripture and philosophy, a common critique targets the environmental degradation associated with modern festival practices. This criticism, however, frequently commits a fundamental category error, conflating the faith’s essential darśana (worldview) with the socio-pathological deviations of contemporary society. It unjustly characterizes Hindu Dharma as the source of ecological harm when, in fact, the tradition itself is a victim of adharmic misinterpretation, commercialization, and a decaying civic consciousness, often driven by a post-colonial, consumerist economy that delinked traditional crafts from their sacred, ecological context.

This dissonance is starkly illustrated in festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi and Holi. The traditional visarjan (immersion) of a mūrti sculpted from river clay and colored with organic turmeric was a perfect enactment of the pañcamahābhūta doctrine, symbolizing the cyclical return of the elements to their source. Today’s mass-produced idols, made from toxic plaster of Paris and industrial paints, are a profane substitute. Their immersion is not a sacred dissolution but an act of permanent pollution that introduces viṣa (poison) into the ecosystem, violating the core Hindu value of śauca (purity). Similarly, the replacement of fragrant, flower-based colors of Holi with synthetic chemicals severs the festival’s connection to the rhythms of the seasons (ṛtu) and the vibrancy of the natural world. These are not scriptural mandates but material corruptions driven by a commercial ethos detached from dharmic principles.

Grand religious pilgrimages, such as the Mahakumbh Mela, face similar scrutiny for their immense environmental toll [17]. Yet again, the issue is not the act of tīrthayātrā (pilgrimage), a journey for spiritual merit and renewal, but the failure of modern infrastructure coupled with a collapse of communal responsibility. The sacred belief in the Ganga’s self-purifying power (pāvana) has been perversely exploited to justify large-scale negligence, ignoring the co-equal emphasis on external and internal cleanliness (śauca) that is foundational to a dharmic life. This represents a crisis of application, not theology.

Crucially, what critics often ignore is the vibrant, internal dharmic renaissance already underway within Hindu communities to rectify these issues. The growing movement among artisans to return to biodegradable clay mūrtis and the promotion of herbal colors are not merely “eco-friendly” trends but acts of reclaiming and revitalizing sāttvic (pure, harmonious) traditions [18]. These initiatives reflect a conscious reinterpretation of paramparā (tradition) through the lens of environmental dharma, proving that the principles for reform lie within the faith itself.

Ultimately, the root issue is not religion but a crisis in civic culture, where the unbridled pursuit of commerce (artha) has become delinked from the ethical guidance of dharma. The fact that Hindu festivals celebrated in the diaspora are often cleaner further indicates the problem is one of localized implementation, not inherent ideology [19]. Therefore, rather than condemning a profound spiritual heritage, a more constructive approach must acknowledge the ecological wisdom it contains and direct efforts toward education and infrastructure that empower practitioners to live in alignment with it.

Putting It All Together

Hindu Dharma’s vast scriptural, philosophical, and ritualistic traditions converge to articulate a profound and comprehensive sacred ecology. It is a worldview that sanctifies the entirety of creation, seeing nature not as a resource for exploitation but as the vibrant, manifest body of the divine. From the Vedic hymns that envision the Earth as a sentient mother (Bhūmi) and the cosmos as the anatomy of the Virat Purusa; to the Upanishadic realization of a non-dual reality (Brahman) where harming nature is a metaphysical self-injury; from the ethical imperatives of ahiṃsā and dharma that demand compassionate alignment with cosmic order (ṛta); and through the seasonal festivals that enact this covenant with Prakṛti: Hindu Dharma advances a life lived in conscious, sacred alignment with the Earth.

The modern ecological transgressions committed during some contemporary festivals are therefore not expressions of this sophisticated theology, but profound betrayals of it. These lapses represent a manifestation of adharma, where the sāttvic harmony of traditional practice has been corrupted by tāmasic ignorance and the excesses of commercialism. This is a sociological pathology, born of a ruptured civic awareness, not a theological principle. Thankfully, a dharmic resurgence is underway, as a growing movement within the global Hindu community works to restore this sacred connection, using both ancient wisdom and modern innovation to realign its practices with its foundational values.

As humanity confronts an unprecedented ecological crisis, a symptom of a deeply fractured relationship with the natural world, it is all the more urgent to revisit the spiritual technologies contained within Hindu dharma. The time has come to re-sacralize our perception and to recover the divine not only in temples and texts but in the very fabric of existence: in the trees, rivers, mountains, and skies. By embracing Hindu Dharma’s original ecological teachings and creatively modernizing their application, its practitioners can lead the way in cultivating a just, balanced, and reverent relationship with the planet. Ultimately, this is the essential praxis of vasudhaiva kutumbakam: recognizing that ‘the world is one family’ is not merely a poetic ideal, but an ecological and soteriological mandate upon which our collective survival depends [20].

References

[1] Atharva Veda. SRI AUROBINDO KAPALI SHASTRY INSTITUTE OF VEDIC CULTURE https://lakshminarayanlenasia.com/articles/Atharva_Veda.pdf

[2] Prime, R. (2014). Hinduism and ecology: Seeds of truth. New Age Books.

[3] Desk, T. L. (2024, August 7). 6 holy rivers in India with incredibly positive energies. The Times of India; https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/soul-search/6-holy-rivers-in-india-with-incredibly-positive-energies/photostory/112335039.cms

[4] Eck, D. L. (2012). India: A sacred geography. Harmony Books.

[5] In Tying a Sacred Thread, Indian Villagers Restore Their Forests – Hindu Press International. (2022). https://www.hinduismtoday.com/hpi/2022/10/22/in-tying-a-sacred-thread-indian-villagers-restore-their-forests/

[6] Dwivedi, O. P. (2000). Classical Hindu views on environmental stewardship. In C. K. Chapple & M. E. Tucker (Eds.), Hinduism and ecology: The intersection of earth, sky, and water (pp. 3–21). Harvard University Press for the Center for the Study of World Religions.

[7] Atharva Veda: Book 12: Hymn 1: A hymn of prayer and praise to Prithivī or deified Earth. (n.d.). https://sacred-texts.com/hin/av/av12001.htm

[8] Klostermaier, K. K. (2007). A survey of Hinduism (3rd ed.). State University of New York Press.

[9] Chandogya Upanishad, Verse 3.14.1 (English and Sanskrit). (2019, January 4). https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/chandogya-upanishad-english/d/doc239005.html

[10] Rambachan, A. (2015). A Hindu theology of liberation: Not-two is not one. State University of New York Press.

[11] Kothari, K. (2016, November 22). Isavasya Upanishad — Commentary Part 1 of 5 by Prof V. Krishnamurthy. Vedanta Thoughts. https://vedantathoughts.wordpress.com/2016/11/22/isavasya-upanishad-commentary-part-1-of-5-by-prof-v-krishnamurthy/

[12] Jain, P. (2011). Dharma and ecology of Hindu communities: Sustenance and sustainability. Ashgate Publishing.

[13] BG 7.19: Chapter 7, Verse 19 – Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God – Swami Mukundananda. (2025). Holy-Bhagavad-Gita.org. https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/7/verse/19/

[14] Chapple, C. K. (2002). Nonviolence to animals, earth, and self in Asian traditions. State University of New York Press.

[15] Leah, J. (2024). Ahimsa | EBSCO. EBSCO Information Services, Inc. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/ahimsa

[16] Gadgil, M., & Vartak, V. D. (1976). The sacred groves of Western Ghats in India. Economic Botany, 30(2), 152–160.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862961

[17] Dixit, K. (2025, February 14). Over 11K tons of waste cleared in 30 days of Maha Kumbh. The Times of India; https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/allahabad/over-11k-tons-of-waste-cleared-in-30-days-of-maha-kumbh/articleshow/118256574.cms

[18] Borges, A.-K. (2017). The ‘Green Ganesha’: The religious and social framing of an environmental movement in Mumbai. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 32(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2017.1256372

[19] Williams, R. B. (1984). A new face of Hinduism: The Swaminarayan religion. Cambridge University Press.

[20] Prakash, A. (2023, February 10). Friday Focus: Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam. https://www.uaf.edu/news/friday-focus-vasudhaiva-kutumbakam.php

![[ India Today ] Ohio senator JD Vance thanks wife, a Hindu, for helping him find Christian faith](https://hinduvishwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/us-senator-jd-vance-reveals-how-his-hindu-wife-usha-helped-him-find-his-christian-faith-image-re-272530504-16x9_0-120x86.webp)