Insights from an Indic scholar on India’s embrace of diverse communities

This article is based on one of his interviews with Dharma Explorers. A complete video recording of the interview can be accessed here at

- Dr. Nathan Katz, a distinguished scholar of Indic studies, discusses his academic journey, extensive contributions to Indo-Judaic studies, and his experiences in India.

- Highlighting the harmonious coexistence of Jews in India, Katz recounts his experiences with the Jewish community in Kochi, emphasizing their dual identity as proud Jews and Indians, and the acceptance and lack of anti-Semitism they experienced.

- Katz elaborates on the similarities and differences between old religions like Hinduism and Judaism and newer, more missionary-oriented religions, discussing their respective approaches to spirituality, tradition, and proselytization.

- Katz reflects on India’s long-standing tradition of welcoming and integrating diverse religious and cultural communities, contrasting it with the history of persecution faced by Jews in Europe and emphasizing the importance of mutual respect and understanding between different faiths.

Dr. Nathan Katz is a distinguished professor emeritus at Florida International University. He also served as the Bhagwan Mahaveer Professor of Jain Studies, Director of Jewish Studies, and founding Chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Born in Philadelphia and raised in Camden, New Jersey, Nathan earned his BA from Temple University in 1970. He spent two years in India studying classical languages before returning to Temple for graduate studies in religion. He was a Fulbright dissertation fellow in Sri Lanka and India from 1976 to 1978 and received his PhD in 1979.

Nathan has taught at many prestigious schools, ultimately joining Florida International University, where he started the Department of Religious Studies. He also helped launch programs in Jewish Studies, Asian Studies, Gender JAIN Studies, and the Study of Spirituality. He is best known for his work in Indo-Judaic Studies and has written several books on the subject. Nathan has also been an adjunct professor of Hinduism at the Hindu University of America and taught at the Sivananda Yoga Ashram in the Bahamas. Currently, he is the Dean of CYS College of Jewish Studies.

Nathan has received numerous awards and accolades, including being a finalist for ‘Who Are The Jews of India?’ and winning the 2004 Vyasa Award from Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan Vak Devi Saraswati Award from India. He received the President’s Award for Achievement and Excellence and Florida International University’s Faculty Senate Awards for Research and Service. He was named Scholar of the Year by the University of South Florida in 1992.

The West often portrays Hindus as polytheistic, whereas Hindus themselves do not care for or about such descriptives. Fundamentally, they see divinity in everything, including inanimate objects, which accounts for their inclusiveness. The question is, why should anyone care how Hindus or followers of other faiths relate to the divine? Do you think the perception of Hindus as polytheistic is why there is so much missionary activity directed towards them?

In 2007, a significant event occurred that planted the seeds of change in interfaith dialogue: the Hindu Dharma Acharya Sabha invited the Chief Rabbinate of Israel to send a delegation to New Delhi for discussions. This was followed by a reciprocal invitation from the Chief Rabbinate for the Hindu Dharma Acharya Sabha to visit Jerusalem in 2008. This series of exchanges marked the beginning of a profound interfaith dialogue between Hindu and Jewish religious leaders.

One of the key figures in these discussions was former Chief Rabbi of Ireland, David Rosen, a respected and well-known figure within the Jewish community. Before the meetings, Rabbi Rosen visited me in America to gain a deeper understanding of Hinduism from someone familiar with both Jewish observance and Indian religious scholarship. Our conversation was part of his preparation to engage meaningfully with the Hindu leaders in India.

The dialogue sessions in New Delhi and Jerusalem were intense and productive, leading to a groundbreaking joint statement. This statement acknowledged the worship of one supreme being in both religions, clarifying that Hinduism’s diverse deities and icons represent different aspects of the same singular divinity, much like how different streams merge into one ocean. This was a pivotal moment because it recognized that both traditions, despite their apparent differences, ultimately share common spiritual goals and values.

Most significantly, the rabbis admitted to seeing similarities in how the supreme being is conceptualized in both faiths, challenging long-held perceptions within their community. They learned that Hinduism’s diversity, often mistaken for polytheism, was actually a form of monotheism, a revelation that came from directly engaging with and listening to Hindu scholars. This interaction underscored the importance of listening and learning directly from adherents of other faiths rather than relying on second-hand interpretations.

The rabbis shared insights from their traditional sources that supported this view, arguing that while Jews have direct commandments from their historical experiences, such as the revelation at Mount Sinai, other religions might use different symbols or rituals to connect with the same divine presence. This mutual recognition fostered a deeper understanding that all righteous believers, regardless of their religious affiliation, share a potential place in the spiritual realm, or what might be called heaven or moksha, in different traditions.

This revelation was not just theoretical but had practical implications for how religious teachings are approached and understood. It demonstrated that the older, established religions have the capacity to recognize and respect the depths of each other’s core teachings, which can sometimes be lost in newer religions that focus more on expanding their reach and doctrine.

My personal academic journey, enriched by learning directly from Indian scholars and texts, has shown me that profound religious insights often come from direct engagement and dialogue, not just solitary study. In universities and scholarly settings, we often debate and discuss religious texts to challenge and refine our understanding, a practice common in both Hindu and Jewish traditions.

When people talk about Hinduism, they often think of it as one monolithic set of beliefs. But just like Judaism, there are many forms and expressions within Hinduism. Scholars today talk about “Judaisms” and “Hinduisms” to reflect this diversity. Religions are not single, unchanging entities; they have many streams and interact with each other.

While studying Jews in India, I found that Jewish texts from the first century not only discuss Hinduism but do so with great admiration. It’s fascinating that these early writings are so positive yet often overlooked. Jews and Hindus have had commercial exchanges for at least 2,000 years, possibly longer. It’s not a recent discovery. While views have varied over time, many Jewish scholars have had a positive attitude toward Hinduism despite the debate over polytheism versus monotheism—a debate influenced by Christian thought.

As an aside, one of my students explored these interfaith dialogues in his master’s thesis, analyzing the supporters and controversies involved, including the roles of NGOs and other organizations impacting foreign policies. His study highlighted the concurrent strengthening of India-Israel relations. Interestingly, a recent survey in Israel revealed that 82% of Israelis favor India as their most liked country, underscoring the deep affection between the two nations.

The enduring bond between Jews and Indians spans thousands of years, though not all details are widely known. In my experience, even while simply walking down the street, I often encounter Indians who recognize and approach me with warmth, curious to learn about Jewish culture and achievements, such as our disproportionate share of Nobel Prizes. This interaction highlights mutual respect and a keen interest in understanding how such a small community has contributed so significantly to global knowledge. This respect also stems from a traditional Jewish emphasis on rigorous intellectual training, a value we cherish and continue to uphold across our community.

We call ourselves Sanatana Dharma or Hindu Dharma, but we’re widely known as Hinduism. Similarly, there are other “isms” like Jainism, Sikhism, Buddhism, and Shintoism. However, it is interesting that two of the 3 Abrahamic faiths do not use the ‘ism’ suffix. They are called Christianity and Islam and not “Christism” or “Muhammadism.”

Do you think there’s a subliminal message here? I looked up “ism” in the dictionary, and it says “an oppressive and especially discriminatory attitude or belief.” Could this be a message being passed on at a subliminal level?

Wow…I did not know ‘ism’ implied what you just said!

Let’s talk about a rather painful subject: antisemitism and Hinduphobia. Jews have faced blood libel for 2,000 years, and now Hindus are being painted with a similar brush—oppressive, destructive, and genocidal. From your perspective, how can we address this corrosive phenomenon that has been around for a long time but is becoming more intense in modern times? How can our communities come together to tackle it?

In these challenging times, the attacks and intimidation both Jews and Hindus face are unlike anything I have witnessed in my lifetime. We are in dire need of strong, respected allies, and India stands out as an essential partner in this regard. The friendship between the Indian and Israeli political leaders is heartening, yet I hope to see this solidarity reflected more consistently in international policies, particularly at forums like the UN.

The similarities between anti-Semitism and anti-Hindu sentiments are striking, with both forms of bigotry employing similar stereotypes and accusations that hark back to old, hateful narratives. Such prejudices often stem from jealousy over the achievements of both communities, who are known to excel in various societies due to their hard work and dedication. Sadly, those who harbor resentment towards us often do so because they cannot fathom the effort required to achieve such success, preferring instead to believe we succeed by unfair means.

Today’s level of hostility is profoundly alarming. As someone who isn’t new to observing world events, I find the current wave of hatred to be deeply concerning, and I wish I had the answers to eliminate it. We must strive to strengthen our bonds and support each other in these trying times, promoting understanding and cooperation against the forces of intolerance and ignorance.

You mentioned that antisemitism and Hinduphobia seem to come from the same playbook. Do you think it’s time for our communities to come together and fight these issues as one phenomenon rather than separately? How can scholars like you help promote this common approach?

When troubling events occur in Israel, the Jewish community here often gathers for demonstrations, a practice that began about 20 years ago. I’ve noticed an increasing number of Hindu participants at these events, which is truly heartening. Alone, our voices may seem like whispers, but together, they resonate powerfully. This unity recalls Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s march in Birmingham, where figures like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel stood by him, showcasing a united front. Such alliances across different communities underscore a powerful message of solidarity and can profoundly influence public perception and responses. It’s crucial that we continue to show up, sign petitions, and be visible in these movements.

With the world in increasing conflict, do you think religion is truly a solution, or could it be the root cause of many of these conflicts?

It’s both. Yes, it can help solve problems, but it also causes problems. I’m not sure if the root is really religious disagreement because those issues often get used for political purposes, even though they’re not inherently political.

Some time ago, I was in a film about Muslim-Jewish dialogue. One of the Muslim participants was a friend. We discussed many common issues and potential solutions for the Middle East.

Recently, that same person, who I thought was on the same side as me, now has opposing views. We can’t be friends anymore. These conflicts go deeper than rational thinking. I can’t maintain a friendship with someone who criticizes Israel excessively, especially during the current crisis. As a result, I have significantly fewer friends now, which makes me sad.

Forgive me for asking, but do you think the “mono” aspect of monotheistic faiths contributes to conflicts, with its “my way or the highway” mentality?

Let’s face it: Muslims and Christians learned from us but got some things wrong. Yes, the idea of one God is very important to us. However, if the Swamis, Hindu Dharma, or Chinese beliefs are correct, then they also have value. As I’ve retired and grown older, I’ve been learning more about Kabbalah and Hasidic meditation techniques. I wouldn’t have reached my current level in Jewish practice without spending years studying Hinduism and Buddhism.

There’s a story about a great rabbi who said that if someone sells coal and someone else sells diamonds, the coal seller won’t care about the diamonds because they focus on their own business. But if they sell sapphires, they can appreciate the beauty and value of the diamonds. This applies to religions too. If you don’t understand the inner dimension of your own religion, you won’t recognize it in others. But if you do, you’ll easily see it elsewhere.

Religion can solve many problems, but it requires much more work and time than most people are willing to invest. You need to understand the heart of your own religion to be open to the heart of other religions. This is why spirituality is challenging; it’s not an easy path.

I think what you’re saying is that seeing faith as a spiritual path is very different from using it as a tool for political power. That takes you to a completely different place.

Absolutely. Spirituality is good, and it should be embraced everywhere, just like in India. When spirituality is present, people respond positively to it, and it helps reduce conflicts between them.

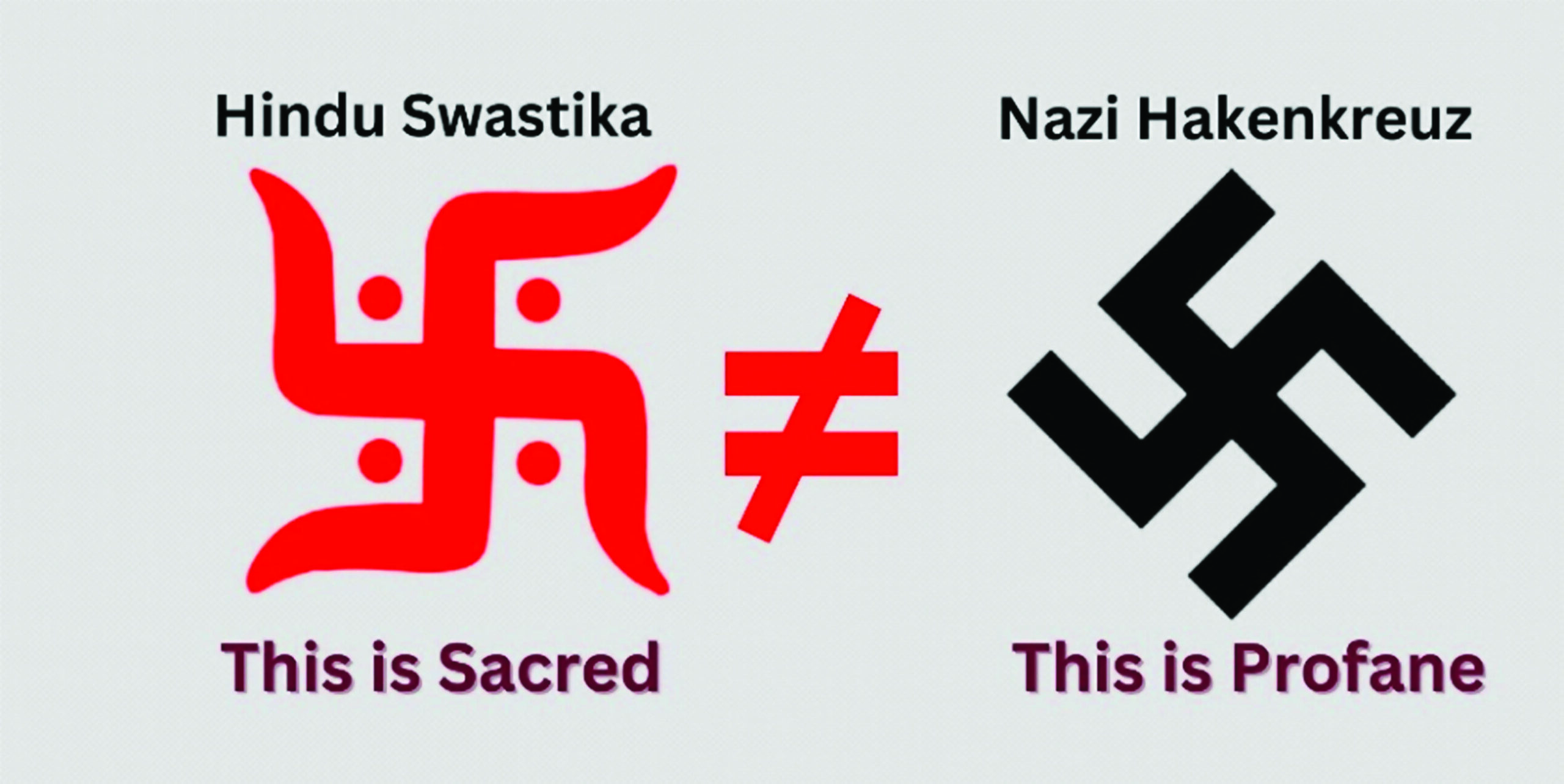

Nathan, I have one important but uncomfortable question to ask. As a Jewish scholar, how do you explain to your Jewish friends the place of the swastika in Hindu Dharma?

In my school office, I had a banner from a temple with the words “Jai Mata Ji” and a swastika on both sides. I displayed it prominently so that when students visited, they would ask about it. This gave me the opportunity to explain the swastika’s original meaning, its use in Native American religions, and how it is a beautiful and profound symbol in its proper context. Unfortunately, Hitler appropriated and defiled it, making it hard for people from my part of the world to see it any other way. It’s difficult but necessary to understand its true meaning.

Visually, the swastika and the Nazi symbol look different, but history has made the swastika a symbol of hatred in Europe. One of my professors wrote about this in a book called “The Cunning of History.” This beautiful, spiritual symbol became something negative through historical events.

I used to feel similarly about the cross. The cross once felt as negative to me as the swastika does to others. Overcoming these feelings requires talking to people. I asked rabbis why they decided Christians are not idolaters, and they said it was through conversations and listening. We need to have many conversations to understand each other.

Most people in America don’t know any Indians, but when they do, it makes a big difference. Being friends with people from different backgrounds allows for honest conversations that touch the heart and bring about change. For example, the dialogue session between the rabbis and swamis, where open and sincere discussions made a significant impact. It’s a slow process, but it can be very effective.

Nathan, I really enjoyed our conversation. I appreciate your kind words about the Jewish experience in India and your scholarly perspective on my faith. This is the kind of conversation our communities need to have on an ongoing basis. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for being so generous with your time.

Thank you for the opportunity. I really enjoyed our conversation.

![[ India Today ] Ohio senator JD Vance thanks wife, a Hindu, for helping him find Christian faith](https://hinduvishwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/us-senator-jd-vance-reveals-how-his-hindu-wife-usha-helped-him-find-his-christian-faith-image-re-272530504-16x9_0-120x86.webp)