Part 1 – Poetry and Literature

In a world bred and brought up on a deeply Eurocentric worldview, any claim of Hindu thought influencing Western culture seems like a chauvinistic boast. Yet a closer examination would show this to be an indisputable fact.

Indeed, there have been numerous pioneers who used art as the medium to bring traditional Hindu ideas to the West. They, in turn, were closely followed by “transmitters who helped spread these ideas across the country. Similarly, there were numerous adapters who took parts of what they received and recast them into their own genres.

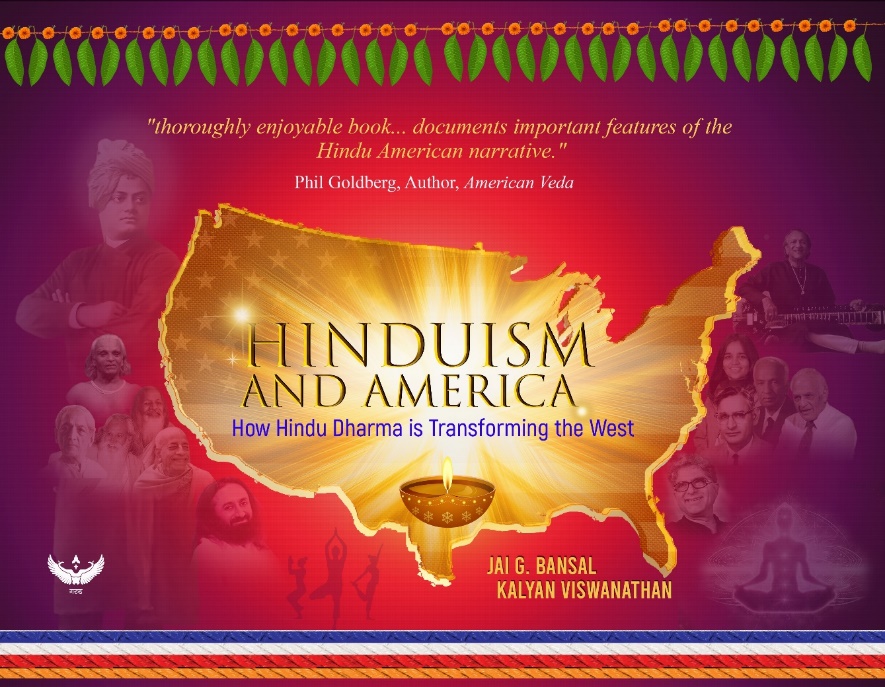

This article gives an overview of how Hindu thought has travelled to the West and has left its indelible mark on the Western literature and performing arts. The article is based on our coffee-table book “Hinduism and America: How Hindu Dharma is Transforming the West.”

Hindu Influence on Western Poetry

Much of the Sanskrit literature has been written in verse form. As it began to be translated into English in late 18th century, it immediately found favour with the litterateurs of the West. As a

result, several Hindu thoughts, concepts and philosophies found their way into Western works. English poetry is no exception, as these examples from the inkpots and feather pens of the romantic poets demonstrate:

“A motion and a spirit, that impels / All thinking things, all objects of all thought, / And rolls through all things.” From ‘Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ (1798) by William Wordsworth.

“The translucence of the Eternal through and in the temporal.” From The Statesman’s Manual (1816) by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

“The One remains, the many change and pass.” From ‘Adonais’ (1821) by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

“To see a world in a grain of sand / And a Heaven in a wild flower / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.” From ‘Auguries of Innocence’ (1863) by William Blake.

While the thoughts and the tone look inspired from the vedic texts, the concepts of infinity, eternity and time have been expounded upon in ancient Hindu scriptures thousands of years ago.

“… it is the “unbroken consciousness of the Self,” the Self that never sleeps, that is never divided, but even when our thought transforms it, it is still the same.” When you come across these words, you could be reading a translation of the Mandukya Upanishad, or you could be going through an essay by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939).

Yeats was drawn to the philosophy of Vedanta when he was around thirty and the attraction grew stronger with each passing year. ‘The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write,’ he mentioned in a letter to John O’Leary. ‘It was my first meeting with a philosophy that confirmed my vague speculations and seemed at once logical and boundless,’ was how he expressed his introduction to Hindu philosophy after listening to Bengali Philosopher Mohini Chatterjee. In his poem Meru (1934), Yeats traces a spiritual journey in search of the “absolute truth” that takes one past the manifold illusions of ‘maya’ and the Path to Desire, and finally, the Path to Renunciation, thus mirroring what the Upanishads say about the inner spiritual journey to discover the ultimate reality. His other works touch upon concepts like karma, transmigration, the various stages of life and the harmony of the inner and outer words.

Another poet on whom the spirituality of Hinduism left a lasting impression was T. S. Eliot (1888-1965). As an undergraduate student at Harvard University, he came in contact with Hindu philosophy while learning Sanskrit from the eminent Sanskrit scholar, Charles Rockwell Lanman. In the coming years, he would explore Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads for their deeper meanings. Numerous references to Hindu concepts, like rebirth, illusion or maya, pain and suffering, especially throughout the cycle of life, have been identified in his poem Wasteland. He also touches upon the concept of non-dualism of Advaita Vedanta and ends the poem with Shantih shantih shantih – a Sanskrit chant for peace.

Hindu Influence on Western Literature – Nonfiction

The advent of the first Vedantic Society in New York in 1894 by Swami Vivekananda was the start of a literary revolution that gradually blended Hindu philosophy into the Western narrative.

Influenced by the simple and yet profoundly liberating philosophy of Vedanta, a generation of writers grew up taking in the wisdom of the Gita, the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali and the Upanishads. Those who were thus transformed would, in turn, transform millions through their writing, helping them gain insights into Hindu thought.

Among these pioneers one name that stands apart is that of Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), a British writer who subsequently relocated to

the US. Introduced by fellow British Writer Aldous Huxley to Swami Prabhavananda’s Vedanta Society, Isherwood collaborated with Swami ji on several literary projects on Vedanta. In 1944 he co-authored with Swami Prabhavananda, their famous book titled Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God, which was feted by Time magazine as ‘a distinguished literary work’ and went on to sell over a million copies. Isherwood produce several other works on Vedanta, such as, Vedanta for Modern Man (1945), Vedanta for the Western World (1949), An Approach to Vedanta (1963), Essentials of Vedanta (1969) and articles which appeared in Vedanta and the West, a bi-monthly journal of the Vedanta Society of Southern California.

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) discovered Vedanta in 1939, and under the guidance of Swami Prabhavananda, learnt the nuances of meditation and spiritual practices. Among the authors who made a particular genre their own, Huxley straddled various literary universes, excelling in science fiction as well as in spirituality. While the dystopian Brave New World (1932), his last novel Island (1962) that created a utopian world in which the inhabitants lived in harmony and practice the philosophy of Vedanta, and The Doors of Perception (1954), an essay collection, elevated him to stardom, his contribution to the West’s understanding of Vedanta offers him a special place in the pantheon of thinkers. In The Perennial Philosophy (1944), Huxley discusses the concept of Sanatana Dharma and concepts like immortality, non-attachment, knowledge of self, temperament, and religion.

Huxley was closely associated with many Vedantists of his time. In particular, he wrote the introduction to the ‘Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God’, a translation of the Bhagavad Gita into English by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, and to The First and Last Freedom (1954) by Jiddu Krishnamurti – a friend, philosopher and guide who changed his life.

Huston Smith, another contemporary author and Vedantist, invited him to MIT where he gave a series of lectures titled ‘What a Piece of Work is a Man’. But it was his 1955 lecture titled ‘Who are

we?’ at the Vedanta Society of Southern California that showcased his depth and interest in key aspects of human existence as discussed in Vedantic scriptures.

Just as Huxley introduced Isherwood to Vedanta, he was initiated into undertaking the spiritual journey by another British writer, Gerald Heard (1889-1971). Like Huxley, he also made the Vedanta Society in Hollywood his campus, home and ashram, from where he would receive his spiritual wisdom and an understanding of the Hindu way of living, which included ahimsa. meditation and vegetarianism.

Heard was instrumental in introducing Huston Smith, a student of his, to Vendatic philosophy. Although Smith was a scholar of world religions, his leaning towards Vedantism is evident from the fact that he begins his famous work, The Religions of Man (1958), with a chapter on Hinduism When Swami Nikhilananda founded the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center in New York,

he not only presented the West with a spiritual hub, but also a life-altering center for several restless writers, one of whom was Joseph Campbell (1904-1987). Campbell’s journey towards spirituality began on a ship where he met a young man named Jiddu Krishnamurti.

As the entire world was gripped in the throes of a second world war, Campbell was looking for peace, and he found it in a translation of the Mandukya Upanishad (1936) by Swami Nikhilananda. In the years to come, Swami and Campbell would collaborate on a book, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (1942), that Time magazine would refer to as ‘one of the most extraordinary religious documents.’ However, the work that made him a legend in the American literature was The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), in which he explored several Hindu concepts and drew from the Bhagavad Gita.

Hindu Influence on Western Literature – Fiction

Indian spiritualism has made its presence felt in numerous works of fiction in the West. In some cases, it has served to inspire, and in others, occupied the centre stage.

Hermann Hesse’s (1877-1962) tryst with the Hindu thought started in early childhood, for his grandparents had been missionaries in India and his mother was born there. Most of his work explores the soul, and the self and that part of the individual that is neither the external shell nor the internal thought.“…those souls that find the aim of life not in the perfecting and molding of the self, but in liberating themselves by going back to the mother, back to God, back to the all.” These words from Steppenwolf hint at the ultimate goal of attaining moksha,

the ultimate liberation from the cycle of rebirth. In Siddhartha, the protagonist realises that it takes a long journey of relinquishment to be able to surrender one’s all, a spiritual journey that takes one past maya and renunciation – two fundamentally Hindu concepts.

Sometime in 1938, renowned author W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) arrived in India, with plans of building his next novel on the foundations of Hindu philosophy. A chance meeting with Sri

Ramana Maharshi set his creative wheels in motion and The Razor’s Edge was born. The protagonist of the novel would be a fictionalised version of the Maharshi. The title of the book itself is a nod to an extract from the Katha Upanishad which says,

“The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over; thus the wise say the path to Salvation is hard.”

The soul-searching journey of the protagonist of this book is the spiritual journey described in Hindu scriptures, while the concept of advaita has been addressed as the search for salvation through realization and knowledge.

Similar Hindu philosophies and insights mark the works of J D Salinger (1919-2010). His last publication, Hapworth 16, 1924, offers an impressive homage to Swami Vivekananda. His short story Teddy featured a ten-year-old who spoke of reincarnation and shared the insights he gained from the Vedanta. The story also highlights the Hindu concepts of renunciation and reincarnation. His last book, Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour-

An Introduction, an omnibus of two novellas, reflects his learnings from Vedanta, with a special focus on the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahansa. Another of his books, Franny and Zooey, explores the depths of Hindu spirituality, both through thoughts and references, referring to karma, atman and chakras. It surely is more than a coincidence that an eponymously titled book on the author divides his life into four parts, based on the four stages of life according to Hinduism – Brahmacharya (Apprenticeship), Garhasthya (Householder Duties), Vanaprasthya (Withdrawal from Society) and Sannyasa (Renunciation).

For a detailed exposition of these and related ideas, please refer to “Hinduism and America: How Hindu Dharma is Transforming the West.”

Dr. Jai Bansal is a scientist, author, and community leader with a keen interest in Indian history and in exploring the contributions of the Hindu civilization to the world. He currently serves as the Vice President of Education for the World Hindu Council of America (VHPA), as well as a member of its executive board and the governing council. After a distinguished career spanning 38 years, Dr. Bansal retired in 2014 as the Chief Scientific Officer and the Global Technology Development Advisor of a global petrochemical company. From 2014 to 2018, he served as an advisor to the Argonne National Laboratory, Chicago, and the US Department of Energy. He holds a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Waterloo, Canada, and a B.Sc. (Distinction) from Panjab University. He has published widely and holds over two dozen scientific patents.

Mr. Kalyan Viswanathan is currently serving as the President of Hindu University of America and guiding its renewal and revitalization. He was a longtime student of Pujya Swami Dayananda Saraswati of Arsha Vidya Gurukulam, established in the Advaita Vedanta Sampradaya and was associated with his work for over 20 plus years. Prior to his involvement with Hindu University of America, Kalyan was a Global Practice Head for one of India’s largest IT Services Company, with a 20-plus year track record. He holds a Master’s Degree in Computer Science and a Bachelor’s Degree in Electrical and Electronics Engineering from BITS, Pilani. He is also working on his Doctoral degree in Hindu Studies, currently, with a scholarly focus on the intersection of Hindu and Western thought, the recovery of Hindu epistemology and its relevance and value for humanity.

![[ India Today ] Ohio senator JD Vance thanks wife, a Hindu, for helping him find Christian faith](https://hinduvishwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/us-senator-jd-vance-reveals-how-his-hindu-wife-usha-helped-him-find-his-christian-faith-image-re-272530504-16x9_0-120x86.webp)